Famous Humpback “Big Mama” Returns to Salish Sea with Eighth Calf

Big Mama and her 2025 calf. Sam Stutz, Eagle Wing Tours

Famous Humpback “Big Mama” Returns to Washington with Eighth Calf

New Calf is First to Be Spotted in Salish Sea this Season

VICTORIA, BC & SEATTLE, WA - May 23, 2025 - The Pacific Whale Watch Association (PWWA) today announced that the first humpback whale calf of the 2025 season has arrived in the Salish Sea. The little one was seen traveling beside its aptly named mother, BCY0324 “Big Mama,” widely beloved for playing a key role in the recovery of local humpbacks. It is Big Mama’s eighth known calf spanning three decades.

The pair was first spotted by PWWA members on Wednesday afternoon in Haro Strait on the US/Canadian border between BC’s Sidney Island and Washington’s San Juan Island, followed by several additional sightings on Thursday. The calf, likely 4-5 months old, stayed close to mom throughout the encounters.

“We’re always eager to see who the first calf of the season will be,” says the PWWA’s executive director, Erin Gless, “and we’re always anxious waiting for Big Mama’s return. This year we got to celebrate both happy occasions at once!”

Humpback calves aren’t born in the Salish Sea. Mothers give birth over the winter in warmer waters off Hawaiʻi, Mexico, and Central America. Big Mama is part of the Hawaiian population. After a few months, mom and baby must travel thousands of miles north to their feeding grounds, dodging fishing gear, shipping traffic, and killer whales, their natural predators. It’s a perilous journey, but one Big Mama has made many times before.

One Whale’s Legacy

“Big Mama is a perfect example of how important a single whale can be to a population,” says Gless. “She was first seen in 1997, and was one of the first humpbacks to return to the Salish Sea after the end of commercial whaling in 1966. She’s been returning ever since, and now has at least eight calves, seven grandcalves, and four great grandcalves. It’s very impressive!”

Two of Big Mama’s previous calves, “Divot”, born in 2003, and “Moresby”, born in 2022, have also recently arrived in the Salish Sea for the season. In the coming weeks, many more humpbacks will return to local waters where they’ll feed on small fish and krill. Humpbacks typically remain in the area through fall before migrating south for winter.

Big Mama and her 2025 calf. Taylor Redmond, PWWA

Big Mama’s 2025 calf breaches. Katie Read, SpringTide Whale & Wildlife Tours

Big Mama’s 2025 calf pokes its head above the water. Sara Shimazu, Maya’s Legacy

Big Mama and her 2025 calf. Andrew Lees, Five Star Whale Watching

PWWA Releases 2024 Sightings & Sentinel Actions Report

A breaching humpback whale Photo: Yasmine Mohammad, Vancouver Whale Watch

New Report Details Salish Sea Whale Sightings, Protective Interventions in 2024

PWWA’s 2024 Report Summarizes 1,351 Sentinel Actions, 43,000+ Wildlife Sightings

SEATTLE, WA & VICTORIA, BC - April 3, 2025 - The Pacific Whale Watch Association (PWWA) has just released the organization’s 2024 Sightings & Sentinel Actions Report. The 38-page annual report summarizes full-year data from the PWWA App, a private wildlife sightings app used by PWWA captains, naturalists, and crew members throughout Washington and British Columbia. The PWWA App is also utilized by researchers, ferry captains, professional ship pilots, emergency response vessels, the Canadian Coast Guard’s Marine Mammal Desk, and the U.S. Coast Guard’s Cetacean Desk.

In 2024, the PWWA App received 43,258 reports of whales and other wildlife in and around the Salish Sea. Bigg’s killer whales were the most frequently documented whale by PWWA App users, seen on 339 days of 2024. Humpback whales were reported on 304 days, followed by gray whales on 205 days, minke whales on 136 days, and salmon-eating Northern Resident killer whales on 110 days. Endangered Southern Resident killer whales were reported on 151 days, but PWWA tours do not focus on Southern Residents, and 83.0% of Southern Resident reports in 2024 were made by researchers, shore-based observers, or vessels from a distance of greater than 1/2 nautical mile (1,013 yards) in Washington state.

In addition to whale sightings, PWWA members documented 1,351 “sentinel actions” in 2024, an increase from 1,246 sentinel actions in 2023. Sentinel actions are protective interventions performed by professional whale watchers during the course of a wildlife tour. Examples of sentinel actions include:

Stopping, slowing, or diverting other vessels near whales

Proactively warning vessels of whales nearby

Removing harmful debris from the water

Reporting sick or entangled animals to authorities

Of 1,351 sentinel actions documented in 2024, 923 (68.3%) involved directly contacting other vessels. Recreational vessels, ferries, and cargo ships were the vessel categories contacted most frequently by PWWA members last year, and the PWWA was successful in slowing, stopping, and/or diverting vessels transiting in the presence of whales in at least 75.5% of vessel-related sentinel actions.

PWWA members also performed 398 debris removals, retrieving harmful items such as balloons, plastic bags, and derelict fishing gear, and 30 sentinel actions categorized as “other”. These other sentinel actions included reporting injured or entangled animals to authorities, and educating fishers and drone operators of current regulations and restrictions.

“This report provides a detailed snapshot of another exceptionally active year for whales and wildlife in and around the Salish Sea,” shares Erin Gless, executive director of the PWWA. “The data our members collect, and the protective role we play on the water, are invaluable. It’s an honor to be part of a professional whale watching community that cares so much.”

The complete PWWA 2024 Sightings & Sentinel Actions Report (19.9 MB) can be accessed here.

A PWWA member flags down an oncoming vessel to warn them of whales. Ellie Sawyer, Maya’s Legacy

A PWWA member holds up balloons retrieved during a tour. Selena Donker, Eagle Wing Tours

New Calf Born to Descendant of Last Orca Captured in Salish Sea

New calf T046B3A surfaces beside mother, T046B3 "Sedna". Tom Filipovic, Eagle Wing Tours (PWWA)

New Calf Born to Descendant of Last Orca Captured in Salish Sea

Baby Boom Continues for Local Bigg’s Killer Whales

SEATTLE, WA & VICTORIA, BC - March 25, 2025 - The Pacific Whale Watch Association (PWWA) announced that a new Bigg’s, or mammal-hunting, orca calf has been spotted in the Salish Sea. The calf was first seen as part of a group of more than a dozen orcas, also known as killer whales, on Thursday, March 20 in eastern Juan de Fuca Strait. It was subsequently resighted several times over the weekend.

“In the images, you can still see fetal folds, along with distinctive orange coloration,” shares Erin Gless, the PWWA’s executive director, referring to creases in the calf’s skin as a result of being scrunched inside its mother’s belly. “These factors are normal and indicate the calf is quite young, likely a week or two at most.”

In all sightings, the calf was swimming directly alongside mother, T046B3 “Sedna”, and has been given the designation T046B3A. It is 14-year-old Sedna’s first known calf. In Inuit culture, Sedna is the Mother of the Sea.

Sedna is part of a well-known family of orcas, a family whose story was nearly cut short almost 50 years ago. In 1976, Sedna’s grandmother, T046 “Wake”, was one of six whales captured and temporarily held by SeaWorld in Budd Inlet, Washington. Ralph Munro, assistant to then Governor Dan Evans at the time, witnessed the captures while sailing with friends and was appalled. Munro helped file a lawsuit against SeaWorld, leading to the whales’ release. They were the last killer whales to be captured in US waters.

Wake is responsible for eight assumed calves, 16 grand-calves, and six great grand-calves. Without the direct efforts of Ralph Munro, at least 30 Bigg’s killer whales would have never been born. Munro went on to serve five terms as Washington’s Secretary of State. His passing at the age of 81 was announced last Thursday, the same day the new orca calf was spotted. Today, Bigg’s killer whales are thriving in Salish Sea waters.

Bigg’s orcas feed on marine mammals such as seals, sea lions, and porpoises. An abundance of food has allowed their population to grow steadily, with more than 140 calves welcomed in the last decade. According to Bay Cetology, a research organization that monitors the Bigg’s orca population, there are nearly 400 individuals in the coastal Bigg’s orca population today, a stark contrast to the endangered Southern Resident orcas who feed on salmon, primarily Chinook salmon, and number approximately 73 individuals. Local whale watch tours focus on thriving Bigg’s killer whales and not endangered Southern Residents.

Visible fetal folds indicate the calf was born very recently. Tom Filipovic, Eagle Wing Tours (PWWA)

T046B3 “Sedna” with new calf, T46B3A. Sam Murphy, Island Adventures (PWWA)

Mom and baby travel side-by-side. Caio Ribeiro, Eagle Wing Tours (PWWA)

Mom and baby were part of a large group of more than a dozen Bigg’s orcas spotted last week. Sara Shimazu, Maya’s Legacy

BIGG’S KILLER WHALE SIGHTINGS UP IN 2024

A large group of Bigg's killer whales. Photo: Jeff Friedman, Maya's Legacy Whale Watching (PWWA)

Bigg’s Killer Whales Drive Increased Salish Sea Whale Sightings in 2024

Humpback Whales Also a Daily Sight in Local Waters

SEATTLE, WA & VICTORIA, BC - August 13, 2024 - Local sightings of Bigg’s killer whales, also known as orcas, are up in 2024 according to the Pacific Whale Watch Association (PWWA) and Orca Behavior Institute (OBI), buoyed by a five-month streak of Bigg’s killer whales being reported every day in the Salish Sea.

OBI, a local research group that compiles whale reports from professional whale watchers, regional sightings groups, and community scientists throughout Washington and British Columbia, recently shared that Bigg’s (mammal-hunting) killer whales have been reported in the Salish Sea every day since March 12, 2024.

“It’s quite the streak,” says Erin Gless, executive director of the PWWA. “Knock on wood, but the season has been very good for viewing killer whales so far.”

July was particularly noteworthy, with 214 unique sightings of Bigg’s killer whales last month alone. “That’s a 70% increase over the 124 unique sightings we had in July 2023”, shares Monika Wieland Shields, director of OBI. OBI defines a “unique sighting” as a sighting of a distinct group of Bigg’s killer whales on a specific day. While the same group of whales may be reported by multiple sources, OBI only counts each group once per day.

A group of Bigg’s killer whales. Photo: Jane Wilson, Ocean EcoVentures (PWWA)

LARGE GROUPS AND NEW CALVES

PWWA whale watch vessels documented several large groups of Bigg’s killer whales last month, some numbering more than 20-30 individuals. One particularly large gathering contained 41 different killer whales from various families all traveling together. Bigg’s killer whales feed on marine mammals, primarily seals, sea lions, and porpoises, all of which are abundant year-round in Washington waters. This bounty of prey has allowed the Bigg’s killer whale population to grow steadily in recent years. According to Bay Cetology, another local research organization, 14 Bigg's killer whale calves have been officially added to the population so far this year - eight born in 2024 and six born in recent years but not documented until 2024. These additions bring the coastal Bigg’s killer whale population to roughly 380 individuals. In contrast, the region’s other killer whales, the Southern Residents, rely on salmon and are endangered, numbering fewer than 75 individuals. Local whale watch tours do not focus on Southern Residents.

Bigg’s killer whales are not the only species delighting whale watchers this season. Humpback whales, which measure the length of a school bus, are also being seen on a daily basis according to the PWWA. A few hundred humpbacks come to the Salish Sea each year to feed on small fish and krill before migrating south in winter.

“We’re fortunate to live in a place where the question isn’t, ‘Will we see whales?’ but rather, ‘Which whales will we see?’”, says Gless. “Nothing in nature is 100% guaranteed, but here in the Salish Sea, the chance of seeing whales is really high.”

A Bigg’s killer whale breach. Photo: Mollie Cameron, Sooke Coastal Explorations

Breaching Bigg’s killer whale T137A “Jack”. Photo: Alli Montgomery, FRS Clipper (PWWA)

Humpback whales are also being seen daily in the Salish Sea. Photo: Sebastian Velasquez, Vancouver Whale Watch (PWWA)

First Humpback Calf of 2024 Spotted in Salish Sea

“Black Pearl” and her 2024 calf. Photo: Clint William, Eagle Wing Tours

First Humpback Mom and Calf of 2024 Spotted in Salish Sea

Famous Humpback Whale “Big Mama” Also Sighted Nearby

VICTORIA, BC & SEATTLE, WA - April 24, 2024 - The Pacific Whale Watch Association (PWWA) announced today that the first humpback calf of the 2024 whale watching season has arrived in the Salish Sea. The calf, likely just three- to four-months old, and its mother, BCX1460 “Black Pearl”, were first seen near San Juan Island on April 18 by PWWA member company Eagle Wing Tours. The pair has been seen several times since in area waters.

“It’s always fun to see which mom and calf will make it back first,” said PWWA executive director Erin Gless. “Black Pearl tends to spend her summers near north Vancouver Island. This year we were lucky enough to spot her in the Salish Sea.”

Humpback calves aren’t born in local waters. Salish Sea humpbacks give birth near Hawai‘i, Mexico, and Central America and then must travel thousands of miles with their babies to cooler feeding grounds. Black Pearl is known to migrate to the Hawaiian Islands in winter, and has been photographed several times off the coast of Maui. She has given birth to at least three previous calves including the most recent, a male born in 2022 nicknamed “Kraken”.

Black Pearl is not the only humpback to return so far this year. The PWWA reports that local whale celebrity BCY0324, known as “Big Mama,” is among a handful of others sighted by whale watchers in the past week. This beloved humpback has proven true to her nickname, giving birth to an impressive seven calves over the years. Big Mama’s first, “Divot”, was born in 2003 and the most recent, “Moresby” was born in 2022. Big Mama’s offspring are also prolific, providing her with at least six “grandcalves” and two “great-grandcalves” so far. She too is part of a population that travels to the Hawaiian Islands during the winter.

“Simply put, she’s the whale who started it all,” continued Gless.

Industrialized whaling removed humpback whales from the Salish Sea by the early 1900s. In all, more than 30,000 humpback whales were killed in the North Pacific during the whaling era, and some scientists estimate as few as 1,000 individuals remained by the time the International Whaling Commission banned commercial hunts for humpback whales in 1966.

“For decades after whaling stopped, there were virtually no sightings in inland BC waters,” Gless said, “but that all changed when Big Mama made her first appearance in 1997. She’s been returning to the Salish Sea ever since, and now hundreds of humpback whales visit each year.”

In the coming weeks, many more humpback whales will return to local waters. They’ll stay to feed on small fish and crustaceans through the fall.

“Black Pearl” and her 2024 calf. Photo: Brooke McKinley, Outer Island Excursions

Famous humpback whale “Big Mama”. Photo: Clint William, Eagle Wing Tours

Humpback whales “Zig Zag” and “Big Mama”. Photo: Mark Malleson, Prince of Whales Whale Watching

New Report Details Whale Sightings, Protective Role of Whale Watchers in Salish Sea

A breaching Bigg’s killer whale. Photo: Sara Shimazu, Maya’s Legacy Whale Watching

New Report Details Whale Sightings and Protective Role of Professional Whale Watchers in Salish Sea

PWWA’s 2023 Report Summarizes 1,200+ Sentinel Actions, Nearly 40,000 Wildlife Sightings

SEATTLE, WA & VICTORIA, BC - April 3, 2024 - The Pacific Whale Watch Association (PWWA) has just released the organization’s 2023 Sightings & Sentinel Actions Report. The 34-page annual report summarizes full-year data from the PWWA App, a private wildlife sightings app used by PWWA captains, naturalists, and crew members throughout Washington and British Columbia. The PWWA App is also utilized by researchers, ferry captains, professional ship pilots, emergency response vessels, the Canadian Coast Guard’s Marine Mammal Desk, and the newly-launched U.S. Coast Guard’s Cetacean Desk.

In 2023, the PWWA App received nearly 40,000 reports of whales and other wildlife in and around the Salish Sea. Bigg’s killer whales and humpback whales were the two whale types most frequently documented by PWWA App users. Bigg’s killer whales were seen almost daily, documented as present in the Salish Sea on 332 days of 2023. Humpback whales were reported on 309 days. Minke whales were reported on 156 days and gray whales were documented on 131 days. Salmon-eating resident killer whales were seen least frequently, with Southern Resident killer whales reported as being present on 111 days and Northern Resident killer whales reported on 77 days.

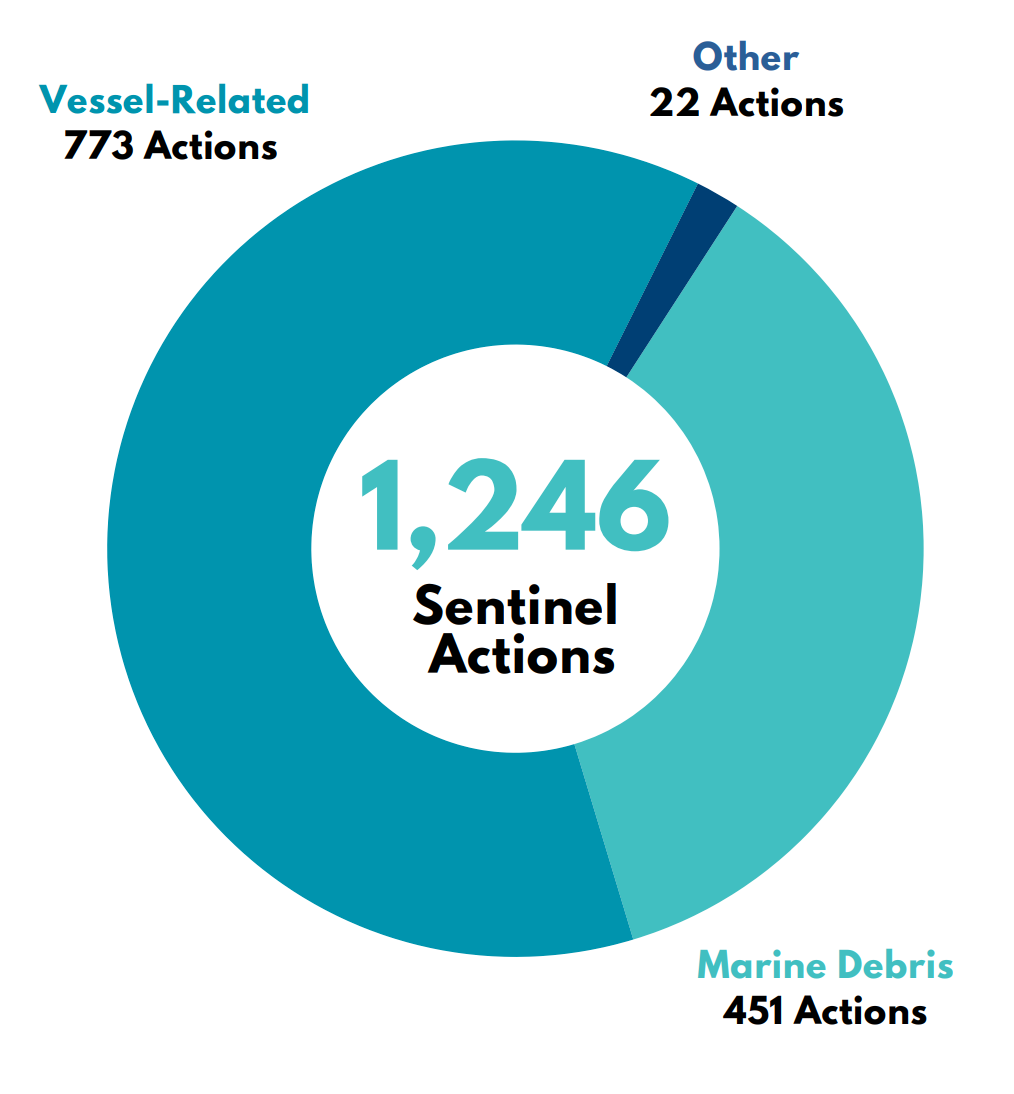

In addition to whale sightings, PWWA members documented 1,246 “sentinel actions” in 2023. Sentinel actions are protective interventions performed by professional whale watchers during the course of a wildlife tour. Examples of sentinel actions include:

Stopping, slowing, or diverting other vessels near whales

Proactively warning vessels of whales nearby

Removing harmful debris from the water

Reporting sick or entangled animals to authorities

Of 1,246 sentinel actions documented in 2023, 773 (62%) involved directly contacting other vessels. The PWWA was successful in slowing, stopping, or diverting nearby vessels in the presence of whales in at least 78% of vessel-related sentinel actions, resulting in safer conditions. This was an increase over 2022’s success rate of 74%.

Last year, PWWA members retrieved more than 451 pieces of harmful debris such as balloons, plastic bags, and derelict fishing gear. The PWWA also documented 22 additional sentinel actions categorized as “other”. These other sentinel actions included alerting authorities of injured or entangled wildlife, reporting oil spills, and assisting boaters in distress.

“This report highlights and quantifies the amazing efforts of our association and its members”, says Erin Gless, executive director of the PWWA. “Not only are we able to educate and inspire guests during our whale watch tours, but we’re also able to protect the wildlife we care so much about. It’s a win/win.”

The complete PWWA 2023 Sightings & Sentinel Actions Report (17.9 MB) can be accessed here.

A PWWA vessel flags down a private boat traveling too fast near whales. Photo: Ellie Sawyer, Maya’s Legacy Whale Watching

Guests aboard a PWWA vessel display a retrieved Mylar balloon. Photo: Val Shore, Eagle Wing Tours

2023 Another Record-Breaking Year for Bigg’s Killer Whale Sightings in Salish Sea

Bigg’s Killer Whale “T-Party”. Credit: Bethany Shimasaki, Western Prince Whale Watching

2023 Another Record-Breaking Year for Bigg’s Killer Whale Sightings in Salish Sea

Previous Sightings Record Smashed with Two Months Still Remaining in 2023

SEATTLE, WA & VANCOUVER, BC - November 8, 2023 - 2023 is already a record-breaking year for sightings of Bigg’s, or mammal-hunting, killer whales, according to the Pacific Whale Watch Association (PWWA) and Orca Behavior Institute (OBI).

OBI compiles whale sightings reports from professional whale watchers, regional sightings groups, and community scientists throughout the Salish Sea of British Columbia and Washington State. Based on these reports, which are confirmed with photographs, there were 1,270 unique sightings of Bigg’s killer whales in the Salish Sea this year through October 31. This surpasses the previous annual record of 1,220 unique sightings, set in 2022, with two months still remaining in the year. According to OBI, a “unique sighting” is a sighting of a distinct group of Bigg’s killer whales on a particular day. While the same group of whales may be reported by multiple sources, OBI does not count duplicate sightings toward their official count, making the volume of Bigg’s sightings this year all the more impressive.

“Ten years ago, we were only getting 15% of that”, shares Monika Wieland Shields, director of OBI. “This is the ninth year out of the last ten that the record has been broken. Only 2020 showed a slight dip, probably due to decreased observation due to Covid-19.”

“What’s happening with Bigg’s killer whales right now is truly remarkable to witness,” says Erin Gless, executive director of the PWWA, a group of 30 professional ecotourism companies with a commitment to education, conservation, and responsible wildlife viewing throughout the Salish Sea. “People once referred to them as ‘transient’ killer whales because sightings were so rare”, continues Gless, “but now we’re seeing them almost daily, and we have their food to thank for that.”

Bigg’s killer whales feed on marine mammals, primarily seals, sea lions, and porpoises. Considered competition with local fisheries, sea lions and harbor seals were once the targets of government-funded bounty programs in Washington, Oregon, Alaska, and British Columbia. The bounty programs ended in the 1960s and 1970s, and seals and sea lions, along with all marine mammals, are now protected in both the US and Canada. Since their protection, populations of seals and sea lions have rebounded in the Salish Sea, luring Bigg’s killer whales into local waters, much to the delight of whale watchers.

When it comes to the region’s other killer whales, salmon-eating Southern Residents, the trend is quite different. “It’s looking like it will be the second lowest year for their presence on record, with only 2021 coming in with fewer days,” says OBI’s Shields.

Chinook salmon, the preferred prey of endangered Southern Resident killer whales, have declined in both size and abundance over recent decades, threatened by rising ocean temperatures, loss of spawning habitat, chemical pollution, and predation from dozens of natural predators, including humans.

“Until we restore the major Salish Sea Chinook salmon runs,” says Shields, “particularly on the Fraser River, it's clear the Southern Residents will continue to spend more time on the outer coast where they have the chance to encounter a wider variety of salmon runs from different river systems.”

A Bigg’s killer whale spyhops near Vancouver, BC. Photo: Ashley Keegan, Wild Whales Vancouver

A breaching Bigg’s killer whale. Photo: Brendon Bissonnette, Prince of Whales Whale Watching

A Bigg’s killer whale swims with a Washington State Ferry in the background. Photo: Sara Hysong-Shimazu, Maya’s Legacy

First Humpback Moms & Calves of 2023 Arrive in Salish Sea

Poptart and her first calf. Photo: Sandy Quinn, Prince of Whales Whale Watching, PWWA

First Humpback Moms and Calves of 2023 Arrive in Salish Sea

Whale Watchers Report Return of Humpback Whales to Local Waters for Annual Feeding Season

SEATTLE, WA & VICTORIA, BC - June 22, 2023 - The Pacific Whale Watch Association (PWWA) today announced that the first humpback whale moms and calves of the 2023 whale watching season have arrived in the Salish Sea. In recent days, whale watchers have documented at least three new humpback calves in local waters.

“We’ve been eagerly awaiting news of the season’s first humpback calves,” said PWWA executive director Erin Gless. “We celebrate every whale’s return, but it’s doubly special when they have a new calf in tow.”

Among the new moms are BCY0523 “Graze”, BCX1675 “Strike”, and BCY1404 “Poptart”. Both Graze and Strike also gave birth to calves in 2019 and 2021, but this is the first calf for Poptart, who was born in 2016 to beloved Salish Sea humpback BCY0324 “Big Mama”. As a youngster, Poptart was often seen breaching completely out of the water, reminding whale watchers of the popular breakfast pastry popping out of a toaster. The name stuck, and Poptart has since become one of the most well-known humpback whales in the region.

Local humpback whales don’t give birth in the Salish Sea, but rather travel with their calves from warmer breeding grounds in Hawaii, Mexico, and Central America. Strike has been documented off Isla Socorro, Mexico in winter, and both Graze and Poptart have been photographed off the Hawaiian Islands. The community science platform Happywhale.com alerted the PWWA that both Graze and Poptart had been spotted with potential calves off Maui earlier this spring. Baby humpbacks seen in the Salish Sea are typically born between late December and February, making these three calves between four and six months old.

“Thanks to modern technology, we already expected a few of these whales to show up with calves this season, but it’s nice to get confirmation, and to know they’ve completed the journey safely,” says Gless. “We’ve notified researchers of their arrival here on the feeding grounds.”

Humpback whales feed on krill and small fish, such as herring and candlefish, and typically remain in the local waters through late fall. Last year, a record 34 humpback whale calves were reported throughout the Salish Sea by researchers with the Canadian Pacific Humpback Collaboration.

Big Mama with a young Poptart in 2016. Poptart now has a calf of her own. Photo: Brooke McKinley, Outer Island Excursions, PWWA

Humpback whale “Strike” and her tiny calf. Photo: Melisa Pinnow, San Juan Excursions, PWWA

Humpback whale “Strike” and her 2023 calf. Photo: Val Shore, Eagle Wing Tours, PWWA

The 2023 calf of “Graze”. Photo: Ashley Keegan, Wild Whales Vancouver

Famed Bigg’s Killer Whale “Chainsaw” Returns; New Calf Spotted with T46B

T063 “Chainsaw” spotted in Salish Sea for first time in 2023. Credit: Sara Hysong-Shimazu, Maya’s Legacy

Famed Bigg’s Killer Whale “Chainsaw” Seen in Salish Sea

Whale Watchers Thrilled by Beloved Orca’s Return; New Calf Also Spotted

SEATTLE, WA & VANCOUVER, BC - April 6, 2023 - The Pacific Whale Watch Association (PWWA) today announced that one of most recognizable members of the coastal Bigg’s killer whale population, T063 “Chainsaw”, has returned to the Salish Sea.

“A Chainsaw sighting is a telltale sign of spring,” says Erin Gless, Executive Director of the PWWA. “He makes an appearance at the same time each year. He’s a local celebrity.”

Chainsaw, named for his distinctive jagged dorsal fin, was first spotted on Tuesday morning in Boundary Pass between the Canadian Gulf Islands and Washington’s San Juan Islands. According to Mark Malleson, a local whale researcher and captain for Prince of Whales Whale Watching, Chainsaw was traveling with his presumed mother, T065 “Whidbey”, and another family, the T049As led by matriarch “Nan”, short for Nanaimo. The whales traveled slowly north along the US/Canada border throughout the day, thrilling whale watch crews and guests alike.

“I finally met the man, the myth, the legend,” said Lauren Tschirhart, marine naturalist for San Juan Safaris in Friday Harbor, Washington. “I’ve known about Chainsaw for years, but always missed out on seeing him. Today was my day. We made sure our guests understood how special this encounter was.”

Born in 1978, Chainsaw is considered one of the oldest males in the Bigg’s population at the age of 45. While Chainsaw’s visits to local inland waters are predictable, they are typically brief, lasting just a few weeks at a time. Beyond the Salish Sea, Chainsaw has been frequently documented throughout southeast Alaska where he is also referred to as “Zorro”.

There are nearly 400 Bigg’s killer whales that feed in the waters of Washington and British Columbia. Unlike endangered Southern Resident killer whales who rely on salmon, Bigg’s killer whales can be seen almost daily in the Salish Sea and are increasing in numbers due to the abundance of seals and sea lions in the area. On Sunday, naturalist Tomis Filipovic of Eagle Wing Tours photographed a new calf traveling with Bigg’s killer whale T046B “Raksha” near Port Angeles, WA. If confirmed by researchers, it will be the 35-year-old whale’s seventh calf.

Chainsaw and other Bigg’s killer whales in the Strait of Georgia. Credit: Sara Hysong-Shimazu, Maya’s Legacy

T063 “Chainsaw”. Credit: Trevor Derie, Outer Island Excursions

New calf with Bigg’s killer whale T046B “Raksha”. Credit: Tomis Filipovic, Eagle Wing Tours

T046B family hunting a sea lion. Credit: Stephen Feng, Prince of Whales

PWWA RELEASES 2022 SIGHTINGS & SENTINEL ACTIONS REPORT

Pacific Whale Watch Association Releases Detailed 2022 Summary Report

PWWA Reports 35,000+ Wildlife Sightings, 1,066 Protective Sentinel Actions in WA & BC

SEATTLE, WA & VICTORIA, BC - March 23, 2023 - The Pacific Whale Watch Association (PWWA) has just released the organization’s 2022 Sightings & Sentinel Actions Report. The 34-page report summarizes data from the PWWA App, a private app used by PWWA captains, naturalists, crew, and affiliates throughout Washington and British Columbia.

Last year, more than 35,000 sightings of whales and other wildlife were reported to the PWWA App by professional whale watchers and authorized contributors. Humpback whales and Bigg’s killer whales were the two whale types most frequently documented by PWWA App users, with humpbacks reported on 310 days and Bigg’s killer whales reported on 293 days. Gray whales were reported on 212 days and minke whales were reported on 166 days. Salmon-eating resident killer whales were documented least frequently, with Southern Resident killer whales reported as being present on 139 days and Northern Resident killer whales reported on 75 days.

In addition to whale sightings, PWWA members documented more than 1,000 “sentinel actions”, in 2022. A sentinel action is a protective action undertaken by professional whale watchers during the course of a tour that benefits whales or other wildlife. Samples of sentinel actions performed by the PWWA in 2022 include:

Stopping other vessels from speeding near whales

Proactively warning vessels of whales nearby

Removing harmful debris from the water

Reporting sick or entangled animals to proper authorities

Of 1,066 sentinel actions documented in 2022, 740 (69%) involved directly contacting other vessels. The PWWA was successful in slowing, stopping, or diverting nearby vessels in the presence of whales in at least 74% of sentinel actions, resulting in quieter and safer conditions. PWWA members were also responsible for retrieving more than 300 pieces of harmful debris, such as balloons, plastic bags, and derelict fishing gear.

The complete PWWA 2022 Sightings & Sentinel Actions Report (16.5 MB) can be accessed here.